Shanghai Tower twists one degree of rotation per floor all the way up to the 121st. The tallest building in Asia, and a symbol of China’s powerful

Shanghai Tower twists one degree of rotation per floor all the way up to the 121st. The tallest building in Asia, and a symbol of China’s powerful economy, it has a façade constructed of more than 21,000 individual panels. The complex curved design has one very important feature beyond aesthetics. It lowers the pressure that wind places on the building’s exterior, an attribute important for any skyscraper but especially in Shanghai.

Located on the eastern seaboard of China in the lowlands of the Yangtze River Delta, the city is subject to typhoons and winds that can exceed 70 miles an hour. Given a recent uptick in wind storms and other weather disasters—something the head of the China Meteorological Administration has connected to climate change—it makes sense that this $2 billion tower would be designed with such hazards in mind. Surprisingly, however, the need to adapt to long-term climate change is rarely a factor in building design these days.

“Designing a building today, you evaluate the current energy use and historical patterns,” says Ben Tranel, a principal at Gensler, the architectural firm that designed the tower. “It’s hard to say how that will change in 50 years, and how do we design to that? It’s almost as if the building’s in Pittsburgh today but in 50 years it will be in Arkansas.”

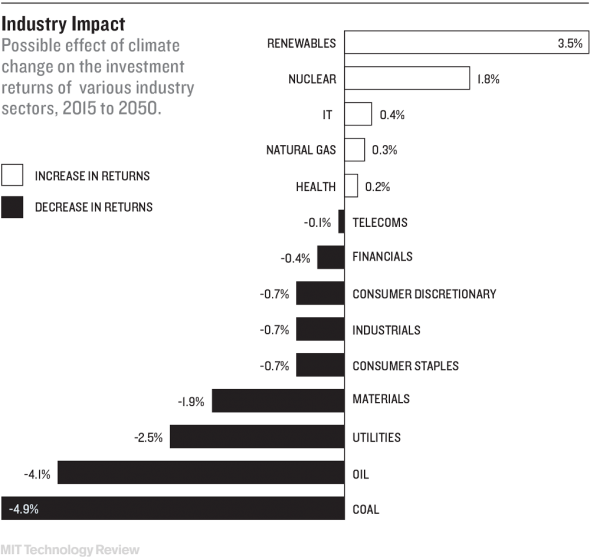

Most industries seem to be in a similar spot: aware that climate change is likely to affect their future but not yet planning for it with any consistency or depth. Long reports have been written about the risks that climate change poses to the economy and to business. But despite calls from leading environmentalists for business to lead the next phase of adaptation, the vast majority of companies are barely in the early days of thinking about this issue.

So in this report we have sought out the exceptions to that rule: the companies and industries that out of necessity or foresight are beginning to plan for a future in which a changing climate will require moving beyond the status quo.

How are they responding to and preparing for climate change? What lessons can others draw from them? These are the central questions of this report.

The industries furthest along are those already dealing with climate change on a daily basis. Among them: agriculture, where temperature and rainfall are already shifting how, when, and where crops are grown, and insurance, where climate experts and actuaries are trying to predict the possible cost of things like increased storm damage, particularly along the coasts of our rising seas.

Some companies’ supply chains are beginning to be disrupted by changing weather patterns. Furniture giant Ikea has suffered disruption from floods in South Asia and lost revenue in mega-storms linked to climate change. So it has set ambitious environmental goals: by 2020 it hopes to produce as much energy as it consumes, using renewable resources like wind farms and rooftop solar installations on its stores.

Global manufacturing companies are making important changes, too. Cars are among the largest emitters of greenhouse gases, and Ford is attempting to minimize its environmental impact and adapt to water shortages at its factories, many of which are in dry places like Hermosillo, Mexico, and Maraimalai Nagar, India. Between 2000 and 2010 the company cut the amount of water used to manufacture a car by one-third. Ford’s water efforts have saved money, so it’s not a hard decision for the company. But there’s always a limit to how far any company will go, says MIT professor Yossi Sheffi. “If there are companies who are willing to lose money or market share or suffer a dip in their valuation in the short term in the name of climate change,” he says, “I did not yet meet any.”

fonte Mit Thecnology Review