The Chinese awakening was one of the central events in the history of the 20th century history. In the penultimate decade of the 19th century, Western

The Chinese awakening was one of the central events in the history of the 20th century history. In the penultimate decade of the 19th century, Western capitalism penetrated China: cheap industrial products damaged local crafts and industries. Social decadence and increasing poverty were worsened by famine and floods in the largely populated rural areas. In the expanding port cities, a revolutionary proletariat and intelligencija were formed. The work of translators such as Yan Fu (1854-1921) brought Chinese intellectuals into contact with modern and contemporary Western thought.

Statesmen such as Kang Youwei (1858-1927) and Liang Qichao (1873-1929) influenced Emperor Guangxu (emperor from 1875 to 1908). His reforms were countered by a reactionary coup d’état on September 21, 1898 by Empress Dowager Cixi (regent from 1861 to-1908), the Emperor’s aunt, which ended the Hundred Days’ Reform. The emperor was put under house arrest; the reformers were executed and the xenophobic Boxer movement was encouraged.

Foreign pressure and domestic political powerlessness led in 1905 to the abolition of the old system based on State examinations for admission to the Civil Service and to the renewal and modernisation of defence led by Gen. Yuan Shikai (1859-1916). Western powers, including Italy, intervened in Chinese internal affairs.

The Alliance Chinese Revolutionary

On August 20, 1905, doctor Sun Zhongshan (Sun Yat-sen, 1866-1925) founded – in Tokyo – the Chinese Revolutionary Alliance (Tongmenghui), a movement that in its programme envisaged the three principles of the people: unity of the people (nationalism); rights of the people (democracy); welfare of the people (socialism). It was spread by the Overseas Chinese, by students and missionary schools, and extended throughout the motherland. On October 10, 1911, the right set of conditions turned a revolt in Wuchang into the Chinese Revolution. To make up for the losses, the Qing court responded positively to a series of demands to turn the authoritarian imperial rule into a constitutional monarchy. Yuan Shikai was appointed as the new Prime Minister, but before he was able to regain the areas conquered by the revolutionaries, the provinces began to declare their allegiance to the ARC. At the time of the uprising Sun Zhongshan was in the United States on a fundraising trip. He went first to London and then to Paris to ensure that neither country gave financial or military support to the government of the Manchurian Qing dynasty (1644-1912). Sun Zhongshan returned to China shortly afterwards. Meanwhile the revolutionaries had conquered Nanking, the former capital of the Chinese Ming dynasty (1368-1644).

Delegates from seventeen provinces arrived for the first National Assembly, which elected Sun Zhongshan as provisional President on November 29, 1911. On January 1, 1912, he proclaimed the Republic of China. Heaven had withdrawn the mandate from the Qing.

The international reaction to the revolution was cautious. During the uprising the countries with investment in China remained neutral, although anxious to protect the rights of the unfair treaties achieved with the Qing through the First and Second Opium Wars. The United States, however, was largely supportive of the republican project, and in 1913, Washington was among the first capitals to establish full diplomatic relations with the new Republic. The United Kingdom, the Japanese and the Russian Empires, etc. followed suit.

Sun telegraphed Yuan Shikai, promising that if he accepted the establishment of the Republic, he would be appointed as President. This was done to win the support of the military for the cause of national unity. Yuan Shikai accepted, thus forcing the court to give him the authority to form a republican government. On February 12, 1912 he acknowledged the abdication of the six-year old emperor Pu Yi (later emperor of the pro-Japanese puppet State of Manchukuo from 1934 to 1945). We will see later why Yuan needed the so-called “continuous permission”.

Meanwhile Outer Mongolia (the present State) had declared its independence (July 1911) – and Tibet, as well (1912) – recognised through the iniquitous Simla Convention (July 3, 1914). Although the new government created the Republic, it did not unify the country under its control. The withdrawal of the Qing led to a power vacuum in some regions. On August 25, 1912 Sun Zhongshan and Song Jiaoren (born in 1882) founded the Guomindang (GMD), the Chinese Nationalist Party derived from the ARC. In the December 1912-January 1913 elections (in which 5% of the Chinese population voted) the GMD won 45.06% of the seats in the National Assembly.

Yuan Shikai probably had Song Jiaoren assassinated on March 22, 1913. Later, relying on 223 AN members out of 870 (who had created the Progressive Party, Jinbudang), he dismissed the GMD provincial governors or forced them to swear allegiance. This was followed by the Second Revolution (July-September 1913), which was suppressed by the government.

Back to the Empire

On November 20, 1915, the end of the Republic of China and the return of the Empire was declared. On December 12, 1915, Yuan proclaimed himself emperor with the name Hongxian. As early as December 25, 1915, public disapproval and people’s aversion to the monarchy were expressed. Japan withdrew its support for the Yuan prince. Some provinces, under the leadership of the Governor of Yunnan, Cai E (1882-1916), rebelled against the new emperor, who renounced the swearing-in ceremony and relinquished his title on March 22, 1916. He died on June 6, 1916.

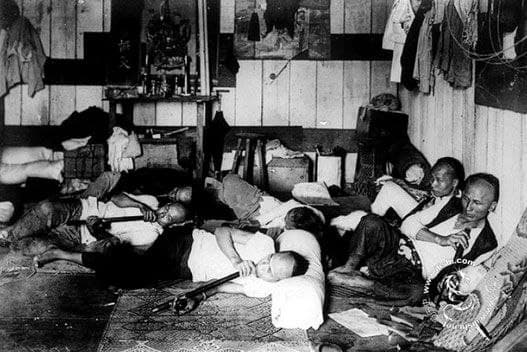

China entered World War I on August 14, 1917, declaring war on Germany, and immediately occupied Qingdao, the largest German naval base abroad, located on the Shandong Peninsula. Yuan Shikai’s death worsened the Chinese crisis, continuing the process of territorial fragmentation. The issue of provincial governors being military and directly controlling their own armies laid the foundations for the period of warlords. Such “feudal lords” often administered their territories without recognising the incumbent government. The numerous generals in the Northern army tried to bring the Beijing government under their aegis. On the other hand, the interference of the States – which had the government finances in their own hands, directly collecting customs duties and gradually granting them to the recognised “legitimate” government after deducting allowances and interest – worsened the bloody internal conflicts. Each power wished to impose its authority on China to the detriment of other foreigners, and for that reason supported one or another of the different warlords.

When the Versailles Conference (January 18, 1919 – January 21, 1920) assigned the German bases in Shandong to Japan, with the backing of the Beijing government, intellectual, literary and political currents called a series of protests throughout the country on May 4, 1919, in which the owners of small and medium-sized enterprises, as well as blue collar workers, participated. The organisers referred to the New Culture Movement, which had originated in 1915 and developed at the Peking University, where the importance of science and democracy was extolled, thus rejecting China’s traditional culture. According to Chinese historiography, the May Fourth Movement marked the beginning of contemporary history. Events followed one another swiftly. Sun Zhongshan established the military government in Guangzhou (Canton, 1921-25). After his death, the national government later moved to Wuhan (1925-27), under the leadership of the rising star Jiang Jieshi (Chiang Kai-shek, 1887-1975).

Communist Party of China

The Communist Party of China (CPC) was founded on July 1, 1921. In 1924 the good relations between the Soviet Union and the GMD led the CPC to create a united front with the GMD. In 1926 Jiang Jieshi launched a successful expedition against the Northern warlords. In 1927 he moved his government to Nanking, broke the alliance with the CPC, and bloodily suppressed the Communists with the Shanghai massacre and the Guangzhou peasant revolts. In 1928 he reunified most of the country. Jiang Jieshi centralised the five powers (the executive, legislative, judiciary, investigation and control ones) into a State Council under his leadership. On August 1, 1927, the CPC founded the Red Army as a form of defence against the GMD attacks.

In 1931 there was the period of the so-called “formative government”: with the Anglo-US support, foreign concessions were regained; extraterritoriality privileges were abolished and domestic duties were eliminated; foreign concessions in Shanghai and foreign control of port duties remained. The government turned into a military dictatorship.

On September 19, 1931 Japan attacked Manchuria. On November 7 of the same year the CPC established the Chinese Soviet Republic in Jiangxi, with Mao Zedong (1893-1976) as Prime Minister. In December 1930 civil war had actually begun. Five annihilations campaigns against the Communists under Jiang Jieshi ended in October 1933 with the Reds being crushed. From October 1934 until the same month of the following year, the Reds launched the legendary Long March of Ten Thousand Li (Changzheng) to move from the then indefensible Jiangxi to Shaanxi. Twelve thousand impervious kilometres covered by the Red Army (later the People’s Liberation Army). One hundred thousand left as against 400,000 and only 20,000 reached their destination.

In 1936 Jiang Jieshi reached the height of his power, controlling 11 of China’s 18 provinces. But on July 7 the Japanese attacked China. In 1937 there was a new agreement between communists and nationalists to combat Japan, the Rising Sun. The GMD government moved from Nanking to Chongqing. Later, once it had fallen into the Japanese’s hands, the collaborationist government of Wang Jingwei (1883-1944), a former GMD member, came to life there. In 1941, Jiang Jieshi – being sure of Japan’s defeat due the entry of his US allies into the war – once again broke the agreement with the communists. In China there were three wars at the same time: the GMD against the CPC, and both separately against the occupiers and the puppet government. Japan surrendered and capitulated on September 9, 1945.

After the end of the Japanese occupation, the Chinese economy was in a very bad state. With the US support, the GMD troops occupied the large cities, but were unable to maintain order. On August 14, 1945 a treaty of friendship and alliance was signed with the Soviet Union, which retained, inter alia, Lushunko (Port Arthur, which was under Soviet-Japanese administration until 1953 and later returned to the People’s Republic of China). Negotiations between nationalists and communists for a coalition government failed. There was renewed fighting between the two factions.

In 1947 the civil war escalated. With the US help, the nationalists held power in vast territories, but the communist troops achieved new successes.

On the eve of May 1, 1948, the CPC’s Central Committee issued an appeal to convene a new conference after the failure of the previous one. Indeed, on October 10, 1945 – in the aftermath of Japan’s defeat – Mao Zedong and Jiang Jieshi had met and agreed on the country’s reconstruction and on convening a consultative political conference. It opened on January 10, 1946 and saw the participation of seven CPC delegates, nine from the GMD, nine from the Democratic League, five from the Youth Party and nine independents.

After reaching the agreement of February 25, 1946 the Conference stalled in July when Jiang Jieshi launched a large-scale offensive against the communist territories with 218 brigades: the real start of further civil war. In December 1947, however, Mao announced that 640,000 nationalist soldiers had been killed or wounded and over a million had laid down their arms.

The appeal of April 30, 1948 was appreciated and immediately echoed by democratic parties, people’s organisations, non-movement personalities and Oveseas Chinese.

On May 5, there were greetings from leaders of various democratic parties including Li Jishen (1885-1959) and He Xiangning (1879-1972) of the GMD Revolutionary Committee – a movement distinct from the GMD as such (the former was its President). Then Shen Junru (1875-1963) and Zhang Bojun (1895-1969) of the Democratic League leadership; Ma Xulun (1885-1970) and Wang Shaoao (1888-1970) of the Chinese Association for the Promotion of Democracy; Chen Qiyou (1892-1970) of the Justice Party; Peng Zemin (1877-1956) of the Chinese Peasants’ and Workers’ Democratic Party; Li Zhangda (1890-1953) of the National Salvation Association; Cai Tingkai (1892-1968) of the GMD Democracy Promotion Committee, and Tan Pingshan (1886-1956) of the Sanminzhuyi Comrades’ Federation (the Three Principles of the People).

Also Guo Moruo (1892-1978), a person with no party affiliation, sent a joint telegram from Xianggang (Hong Kong) to the CPC’s Central Committee, Mao Zedong and the entire nation supporting the communists’ call.

Meanwhile, the Association for the Promotion of Democracy and the Jiu San Society (September 3), which had established their headquarters in areas under the GMD rule, held secret meetings of their central committees to welcome the CPC document.

Mao Dun (1896-1981), Hu Yuzhi (1896-1986), Liu Yazi (1887-1958), Zhu Yunshan (1887-1981) and 120 democrats issued a joint communiqué expressing their agreement with the CPC position. In addition, 55 leaders of the democratic parties and people from outside the party issued joint comments on China’s political situation, stating:

“[…] during the People’s Liberation War, we are willing to contribute and cooperate in designing programs under the CPC’s leadership, expecting to promote the quick success of the Chinese People’s Democratic Revolution for the forthcoming foundation of an independent, free, peaceful and happy New China.”

The Conference held its first plenary session in Beijing from 21 to 30 September 1949. A total of 622 representatives attended. They were sent by the CPC, by democratic parties, independent personalities; mass and regional organisations, the People’s Liberation Army, ethnic minorities, Overseas Chinese, patriotic democrats and religious groups.

The first session exercised the functions of a fully-fledged parliamentary, legislative and constitutional Assembly of the nascent State until 1954, when the first National People’s Congress was elected. The CPC Central Committee adopted the Provisional Constitution (the CPCCC Common Programme), the CPCCC Organic Law and the Organic Law of the Central People’s Government. It chose Beijing as the capital of the country. It established the five-star red flag (Wu Xing Hong Qi) as the national flag: red stood for the revolution; the big star stood for the CPC; the other stars stood for the social classes: workers, peasants, lower middle class and capitalists (national middle class). It adopted the March of the Volunteers (Yiyongjun Jinxingqu) as the national anthem and opted for the Gregorian calendar. The session elected the CPCCC National Committee and the State Central People’s Government Council. On October 1 – through Mao, the NC Chairman – it proclaimed the People’s Republic of China.

The GMD government and army fled to Taiwan. Jiang Jieshi was defeated precisely because he was unable to offer his country a future of independence from the imperialist powers to which he was linked, starting with the United States.

When Heaven withdrew the mandate also from the bourgeois Republic, it was a cyclical change in universal history, comparable only to 1789 and 1917. The manoeuvres of the People’s Republic’s enemies later excluded eight hundred and forty-one million Chinese from the United Nations until 1971.