The major US crude oil benchmark has fallen into a bear market, heaping more pressure on oil companies and major producing countries that had ho

The major US crude oil benchmark has fallen into a bear market, heaping more pressure on oil companies and major producing countries that had hoped the worst of the rout was over.

West Texas Intermediate, the main US crude benchmark, fell to as low as $40.75 on Friday morning, down just over 20 per cent from its intraday peak of $51.67 per barrel on June 9. A 20 per cent decline is the technical definition of a bear market.

Oil prices are still comfortably above the nadir touched at the start of the year and Brent crude, the North Sea benchmark that is the most used international measure, is still hovering just over bear market territory. However, the renewed decline is a worrisome development for energy groups and states that depend on oil revenues.

Here are five things traders are tracking to see if the slide continues — or if the sell-off is just a blip in a recovery.

Supply and demand

Two years since oil began its precipitous decline from above $100 a barrel, reaching a trough below $30 in January, the market appears to be edging closer towards balance.

High-cost supplies are declining, demand has been boosted, and concern about the impact of investment cuts on future supplies have all helped the market recover from levels that threatened bankruptcy and caused economic pain across the sector.

But the process of moving back to a balanced market was never going to be smooth. This summer has disappointed the more bullish analysts as the two-year-old glut of crude has become a glut in products — the gasoline, diesel and jet fuel that consumers use.

Refiners ran hard to meet forecasts of surging demand but may have over-egged just how much fuel was needed. Stocks of both crude and products that havebuilt up over the past two years will need to be worked off before there can be a more sustained recovery.

Gasoline

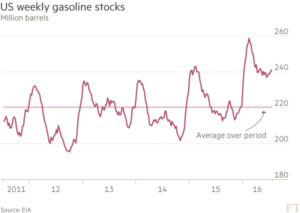

The recent decline in oil prices has several drivers but one stands out: gasoline demand has underwhelmed and stocks of the fuel are too high.

In the US — the world’s most important gasoline market, accounting for almost one in every nine barrels of oil globally — a huge surplus is overhanging the market as the summer driving season draws to a close. Stocks are 12 per cent higher than a year ago.

This is putting pressure on prices and refining margins. If it continues, refiners, who had been running hard for much of the past 18 months as low prices buoyed demand, may decide to buy less crude. That, many fear, is delaying the rebalancing of the market.

This new downstream threat has also sharpened attention on demand, which may now not be growing as quickly as many people assumed.

The US Energy Information Administration recently lowered its gasoline demand growth forecast for the remainder of the year to 130,000 barrels per day, or 1.5 per cent, from 220,000 previously.

Others think it is lower still. Veteran oil economist Philip Verleger reckons US gasoline consumption has increased at a rate of just 1.1 per cent this year compared with 2015.

“The fall in gasoline prices will pull crude prices down,” he says. “In the absence of a disruption, do not be surprised to see Brent falling below $40 a barrel, possibly to $37, by mid to late September.”

Floating storage

The persistence of the oil glut has seen some traders storing crude oil and refined fuels such as gasoline and diesel aboard tankers at sea.

They can partially finance the storage by selling the oil forward through the futures market where it currently fetches a higher price thanks to a structure known ascontango that is prevalent when the market is oversupplied (the opposite structure,backwardation, sees spot prices rise above future prices during times when supplies are tight).

But while the contango currently covers some of the additional cost of hiring vessels it is not yet wide enough to make it a widespread trade like it was during the financial crisis, when a sudden collapse in demand made floating storage the hottest trade of 2009.

Instead, traders and analysts say it has largely been driven by necessity, with onshore storage already very full or locked up by rival traders in long-term deals. Indeed, outside of a few isolated geographic pockets, floating storage has declined in the past month as global supplies start to recede.

Energy Aspects, a London-based consultancy, calculates that floating storage levels for crude and fuel oil have declined by more than 60m barrels since early June, mostly from oil held on water.

“Stocks are drawing down and oil is coming out of storage, albeit the pace has slowed slightly due to high product stocks,” says Amrita Sen at Energy Aspects.

Rig counts

When Saudi Arabia took its fateful decision in December 2014 not to bolster prices by reducing production it did so with a clear aim in mind — to rebalance the market by driving out higher-cost supplies. That put US shale producers, among others, firmly in the crosshairs.

From that date, oil market participants have closely followed the weekly US rig count survey complied by Baker Hughes to assess the pace of the rebalancing process. Though it is an imperfect measure, the number of rigs drilling is a guide to where US production will go after almost doubling from 5m barrels in 2007 to 9.4m barrels last year.

Since hitting a seven-year low of 316 in May, the number of rigs drilling for oil has crept higher, rising to 371. Last week’s gain of 14 was the biggest increase since December. Since crude oil rose above $50 a barrel in June, drillers have put 55 rigs to work.

If maintained, the increase in drilling activity should stop the decline in US oil production. The US Energy Information Administration now thinks crude production will bottom at 8.1m barrels per day in September before edging up to 8.3m b/d in November and December. Oil majors forecast a similar trend.

“In the US, production continues to slowly decline and we anticipate a further drop in the third quarter,” Bob Dudley, BP chief executive, said on Tuesday. “But with producers slowly adding back rigs, production should stabilise by the year-end.”

Hedge fund positioning

After amassing a near-record bet on the recovery in oil prices between January and May, funds have either started taking profits or placed more bets the other way.

In early May, hedge funds held the equivalent of almost 420m barrels of Brent through futures and options contracts. Net longs — the difference between bets on higher and lower prices — have since fallen to less than 300m barrels equivalent.

In the US benchmark West Texas Intermediate there has been a similar pattern, with net longs declining by 100m barrels since late April.

“This has been largely driven by a fairly rapid take-up of short positions by the money managers group, which looks reflective of a broader change in sentiment,” say analysts at JBC Energy in Vienna.

“Inputs on the speculative side are certainly more bearish than bullish and crude fundamentals could certainly be used to make a case that there is some more downside to prices yet to be flushed out.”