Euroskepticism's Biggest Fallacy It is now up to British voters to decide whether the United Kingdom should leave the European Union—not to foreign l

Euroskepticism’s Biggest Fallacy

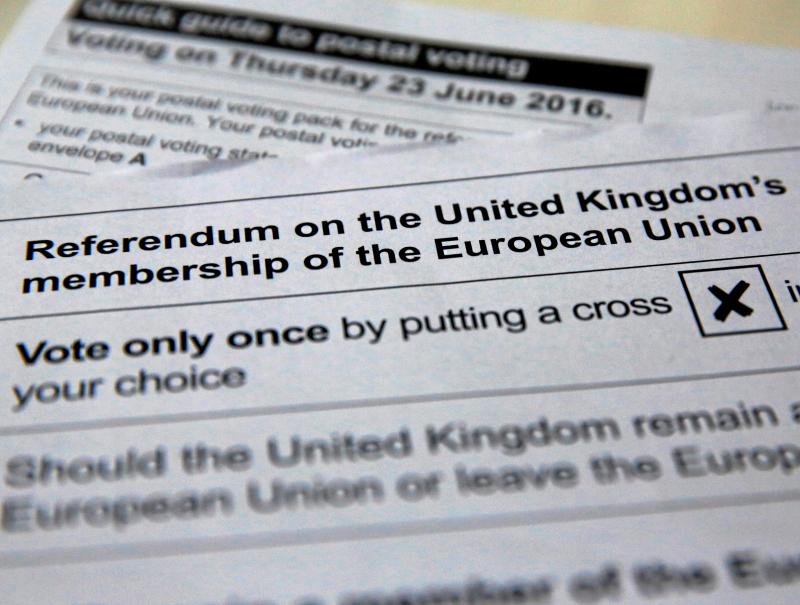

It is now up to British voters to decide whether the United Kingdom should leave the European Union—not to foreign leaders, including U.S. President Barack Obama and IMF head Christine Lagarde, who have offered their advice on what the right choice might be. The voters, however, would do well not to automatically dismiss what Obama and Lagarde have said. Rather, they should reflect on their substantive merits.

The truth is that the case for “Brexit” does not hold water. Although there is much to criticize about the EU, its existence is an important achievement, which would be put in peril by the United Kingdom’s departure from the bloc. Conservatives, classical liberals, and advocates of free markets should be particularly wary of becoming cheerleaders for the EU’s demise. Instead, they ought to be at the forefront of efforts to reform and improve the bloc.

Free-marketeers and small-c conservatives might see Euroskepticism as a natural extension of free-market convictions. For fervent believers in the strength of competition, including between different currencies and regulatory and tax systems, European integration might look like a misguided attempt at integrating markets via the unnecessary centralization of political decision-making. And so it seems logical for the president of the Czech Republic, Václav Klaus, to compare the EU to the former Soviet Union, and for free-market think tanks to criticize the EU’s populist overregulation, common currency, and common agricultural policy, among other things.

But Euroskepticism is not an inevitable corollary of free-market conservative thought—something that the iconic voices of the free-market movement well understood. Friedrich von Hayek wanted a European federation. He called “the abrogation of national sovereignties” that it would entail a “logical consummation of the liberal [i.e. free-market] programme.” Hayek, who later received the Nobel Prize for Economics, recognized that the efforts to liberalize trade in the nineteenth century had ultimately failed because European countries lacked a joint system of governance that would keep domestic protectionism and nationalism at bay.

Even Hayek’s mentor, Ludwig von Mises, who was generally seen as a much more radical free-marketeer than his protegé, wrote in 1944 that for Western European countries, “the alternative to incorporation into a new democratic supernational system is not unrestricted sovereignty but ultimate subjugation by the totalitarian powers.” And, when British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher campaigned for the United Kingdom’s membership in the European Economic Community in 1975, she recognized that “almost every major nation has been obliged…to pool significant areas of sovereignty so as to create more effective political units.”

Today’s world is very different from that of the 1940s or the 1970s. But that does not make the European project irrelevant. Quite the contrary. Even the seemingly economic components of European integration, such as the single market, require a significant pooling of political sovereignty, a bureaucracy, and courts to enforce the rules. In part, this is because a single market goes far beyond the question of the tariffs that, until 1968, separated markets in the countries of the European Economic Area. It has sought to curb regulatory protectionism and other, more subtle barriers to trade, including distortionary state aid spending directed at national champions.

The single market did not arise overnight. It took decades of political and legislative effort, most notably in the form of the Single European Act, spearheaded by Thatcher and Conservative politician and eventual European Commissioner Arthur Cockfield, to reach the degree of economic openness existing in the EU today. The single market is perhaps the most striking example of what the EU does best—namely, that it serves as a commitment device.

When Euroskeptics complain of the constraints that European integration imposes on national sovereignty, they are thus missing the point. European treaties, the entire body of EU law, and the decision-making authorities disentangled from national politics exist for a good reason—to allow politicians in member states to get around the problem of credible commitment, which is pervasive in democracies, and which involves the omnipresent temptation of policymakers to renege on their promises.

To see how, look to Eastern European reformers in places such as Slovakia or Poland who used the prospect of EU accession as a sweetener for domestic reforms that would have otherwise been unpalatable. For countries such as France or Italy, EU policy is often the only thing that keeps their leaders from returning to their countries’ historic traditions of providing state aid to national champions. It was, after all, the European Commission that forced Italy to dismantle its state-owned steel industry in the 1990s and pushed France toward the opening of its electricity market in 1999. Without the United Kingdom’s voice at the table, the EU would inevitably become a much weaker force for economic liberalization, and some of prior achievements could even be reversed.

Euroskeptics have a point when they say that there is a flipside to the single market—namely, the existence of a large and burdensome system of regulation at the European level. It would be much better, they argue, if member states simply recognized each other’s regulations and technical standards without imposing a one-size-fits-all solution on everyone. But unconditional mutual recognition is not realistic—largely because governments are unable to commit credibly to such a policy. Hence, although common EU directives certainly impose a burden on the European economy, that burden needs to be compared against the burden of 28 different and potentially incompatible regulatory systems, hindering free movement of goods, services, capital, and people.

The United Kingdom, with its sizeable sector of financial services, benefits greatly from the “financial passport” that allows its banks and other financial businesses to operate anywhere in the EU. The City of London is also home to the European Banking Authority, an EU-wide financial regulator, over which the United Kingdom has had a significant influence. A departure from the EU could jeopardize these arrangements and raise doubts about the future of the city as the world’s financial capital.

Even the late nineteenth century, sometimes called the First Age of Globalization, was the period of German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck’s “iron and rye” tariff, France’s Méline tariff, and a continent-wide drift toward protectionism. In 1913, tariffs on manufactured goods averaged 18 percent in Austria-Hungary, 13 percent in Germany, 20 percent in France, 41 percent in Spain, and a staggering 84 percent in Russia. At that time, the United Kingdom appeared a free-trading nation in comparison, with no tariffs on manufactured goods and an average applied tariff of around 5 percent on all imports. Yet, throughout much of the nineteenth century, until the late 1870s, the UK was highly protectionist, with average tariffs exceeding those in France.

With the advent of World War I, followed by the Great Depression and then by the bloodiest conflict in human history, international trade essentially collapsed, greatly exacerbating the human misery that characterized the first half of the twentieth century. By that token, the past 70 years of European history, during which Europe has become more economically open, democratic, and peaceful than ever before, are a complete historical anomaly. Whether one believes that the EU deserves any credit for this outcome, one should think twice before trying to tinker with the system of international political architecture existing in Europe.

The United Kingdom’s leadership has been essential for the existence and success of this system, including the single market but also in focusing Europe’s attention to the threats facing the continent, such as the rise of a revisionist Russia. And although the United Kingdom can prosper even outside of the EU, Brexit would inevitably set in motion centrifugal dynamics on the continent, empowering nationalists in countries that have no chance of being successful outside of the EU. Just a few weeks ago, inspired by the upcoming British referendum, 92 out of 200 members of the Czech Parliament voted for the motion—narrowly defeated—to organize a referendum about the departure of the Czech Republic from the EU.

At the present time, Europe is coming under an unprecedented amount of stress. From the economic woes of the eurozone, through the political tensions brought about by the refugee crisis, to Russian President Vladimir Putin’s use of propaganda and energy ties to undermine liberal democracy in Central and Eastern Europe, the continent is at a greater risk of descending into chaos than at any point in its postwar history. That is the real danger facing Europeans today, not the threat of a Pan-European authoritarian superstate.

It is imperative that the proponents of free markets, both classical liberal and conservative, double down on their defense of the international political order in Europe, which has coincided with the continent’s current period of peace, democracy, and prosperity.

Fonte: foreignaffairs.com