Interview with Prof. Giancarlo Elia Valori May 2023 China has been investing heavily in technological innovation, partic

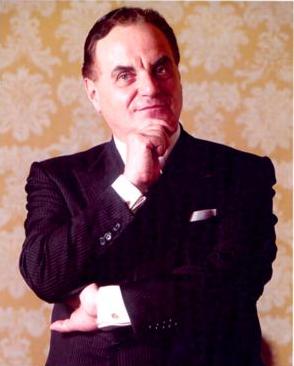

Interview with Prof. Giancarlo Elia Valori

May 2023

- China has been investing heavily in technological innovation, particularly in areas such as artificial intelligence and 5G. How do you see China’s technology industry evolving in the coming years, and what implications could this have for the rest of the world?

In recent years China has delved into the importance and development prospects of artificial intelligence (AI) in many important fields. Stepping up the development of a new generation of AI is an important strategic starting point to stay ahead in the global technology competition.

The current gap between AI development and the advanced international level is not very wide, but the quality of companies must be “matched” by their number. Efforts are therefore being made to expand application scenarios, by strengthening data and algorithm security.

The concept of third-generation AI is already advancing and there are hopes that the security problem will be solved through technical means other than policies and regulations, i.e. mere talk.

AI is a driving force for the new stages of technological revolution and industrial transformation. Accelerating the development of a new generation of AI is a strategic issue for China to seize new opportunities for organising industrial transformation.

It is commonly argued that AI has gone through two generations so far. AI1 is knowledge-based, also known as “symbolism”, whereas AI2 is based on data, e.g. big data, and their “deep learning”.

AI started to be developed in the 1950s with the famous Test by Alan Turing (1912-1954), and the first studies on it started in China in 1978. In AI1, however, progress was relatively small. Real progress has been made mainly over the last 20 years – hence IA2.

AI is known for the traditional IT industry, typically the Internet companies. It has accumulated a large number of users in the development process, thus establishing corresponding patterns or profiles based on these acquisitions, i.e. the so-called “users’ taste knowledge graph” of users. Taking the delivery of certain products as an example, tens or even hundreds of millions of data consisting of user and merchant location information, as well as information about potential buyers, are incorporated into a database and then matched and optimised by means of AI algorithms. This obviously enhances trade efficacy and the speed of delivery.

By updating and upgrading traditional industries in this way, great benefits have been achieved. In this respect, China is leading the way: facial recognition, smart speakers, intelligent customer service, etc. In recent years, not only has an increasing number of companies started to apply AI, but AI itself has also become one of the professional directions that most worries candidates in university entrance exams.

According to statistics, there are 40 AI companies in the world with a turnover of more than $1 billion, 20 of them in the USA and 15 in China.

The core AI sector should be independent of the IT industry, but open up more to transport, medicine, the urban substrate, and industries directed autonomously by AI technology. These sectors are already being developed in China.

China accounts for more than a third of the world’s start-ups in the AI field. While the quantity is high, the quality still needs to be improved, although there are signs that it will evolve geometrically.

The AI implications in today’s world are therefore knowledge and technological advantages that determine – to a large extent – the differences in the management of international politics. The increase in a country’s intellectual power directly defines an increase in its economic power, thus changing its positioning in the international competition for dominance.

The politics of power – first in the agricultural era and later in the industrial era – was characterised by military and then economic hegemony, while the politics of power in the information era gradually reveals the characteristics of knowledge-based hegemony at the scientific level, which will indeed be essentially based on artificial intelligence.

- Some people have accused China of engaging in unfair trade practices, such as dumping goods on foreign markets or stealing intellectual property. What is your opinion on these allegations, and do you believe China should be held accountable for these actions?

In fact, many Western media report that China is circumventing or breaking trade rules. Its economic manipulations have cost millions of US jobs, hurting workers and companies there but also around the world. Media also report that the United States will reject market-distorting policies and practices, such as subsidies and barriers to market access, which the Chinese government has used for years to gain a competitive advantage.

In fact, China has faithfully fulfilled the commitments made when it joined the World Trade Organisation (WTO). China supports, builds and contributes to the multilateral trading system. Economic and trade relations between China and the United States are mutually beneficial. Nevertheless, the economic war between the People’s Republic of China and the United States in the trade and investment areas has been the main cause of trade frictions between the two countries, which harm others without benefiting themselves either.

Over the last twenty years since joining the WTO, China has seriously fulfilled the commitments made upon accession. It has extended the pre-determined national treatment management system to the national level. It has continued to expand market access. It has reduced the overall tariff level from 15.3 to 7.4 per cent, and opened up nearly 120 service sectors.

In October 2021 the WTO conducted its eighth review of China’s trade policies and practices. The review report fully recognised China’s efforts in supporting the multilateral trading system and its active role within the WTO.

A leading official of the UN Conference on Trade and Development pointed out that, over the past two decades, China has firmly supported the rules-based multilateral trading system; practised genuine multilateralism; fully participated in WTO negotiations; led talks in areas such as investment facilitation and e-commerce, and worked for up-to-date WTO rules.

China and the United States have highly complementary economies, deeply integrated interests, and mutually beneficial economic and trade ties. In 2021 bilateral trade exceeded a record USD 750 billion. The US Export Report 2022 released by the US-China Business Council showed that in 2021 exports of goods to China grew by 21% to USD 149 billion, supporting 858,000 US jobs. The Annual Business Survey 2020 report on Chinese companies in the United States, released by the China General Chamber of Commerce-USA, indicated that, as of 2019, Chinese CGCC member companies cumulatively invested more than USD 123 billion, as well as employed over 220 thousand people, and supported more than one million jobs in the United States. A study by the US-China Business Council showed that Chinese exports helped reduce consumer prices in the USA by 1 to 1.5 per cent, saving each US household USD 850 a year.

A report by Moody’s Investor Service was quoted as saying that US consumers bear 92.4% of the cost of imposing tariffs on Chinese products. Paul Krugman – 2008 Nobel Prize-winning economist – has incisively pointed out that the US trade policy towards China is disadvantageous and tariffs hurt the USA more than its intended targets.

On 18 May 2022 the National Retail Federation (NRF) wrote to President Biden asking for the removal of tariffs which, as outlined in the letter, could reduce consumer prices by up to 1.3%. The US Secretary of the Treasury, Janet Yellen, said that some tariffs on China’s products harm US consumers and businesses and that it is worth considering cutting them to lower inflation in the USA.

I believe that – like any war – a trade war is detrimental to both sides and that – unlike the Cold War, when an opponent wanted to impose its own ideologies and forms of government and State on the other – here we end up with a country, namely China, that only demands trade and does not advocate any political revolution.

- China has been rapidly expanding its military capabilities in recent years, with a focus on developing new technologies such as hypersonic missiles and aircraft carriers. What do you think is driving this expansion, and how do you see China’s military posture evolving in the coming years?

With a country of 1.4 billion inhabitants, the Chinese armed forces are inevitably bound to expand and strengthen. Throughout Chinese history, the military has been a fundamental factor not only in the existence of the State, but also in the liberation struggles against Japan and the various doctrines that later tried to isolate the People’s Republic of China, such as Containment, etc. In a world led by a single leader, namely the United States of America, it is important to understand the moves of the States that seek not to be sidelined. China is certainly one of the States that aspire to play at least an equal role in international relations with the USA. The military force that China has been developing over the past fifteen years has seen a significant expansion of its fleet. According to a US study, the need to secure the islands in the South China Sea would be the crux of the whole project. The Chinese island of Hainan is in fact the starting point of a maritime route that would connect China with Pakistan in the Middle East and with Djibouti in the Horn of Africa.

The Chinese strategy is to invest in civil (and not military) infrastructure such as ports, oil pipelines, roads, gas pipelines within allied countries that would thus ensure security and allied bases in the Indian Ocean. Security is a crucial factor in understanding this strategy because since 1993 China has become a net importer of oil (i.e. China’s oil demand is greater than supply) and oil is imported both by land and by sea. The latter option is obviously used with African and Middle Eastern countries, but the trade route is in one of the areas with the highest concentration of sabotage, kidnapping and violence by pirates. Having allies with whom to ensure security in enemy waters becomes therefore crucial. Allied bases, however, also have the function of enabling Chinese ships to have easy and quick passage through three of the world’s richest and most dangerous straits, namely the Bab al Mandeb Strait (between Yemen and Djibouti), the Aden Strait (between Iran and Oman) and the Malacca Strait (between Indonesia and Malaysia).

I do not see why China should not strengthen its strategic potential, since all countries – from the strongest to the medium ones – do so on a regular basis, as a function of planned commercial development. It is only natural that this should also involve the development of new technologies such as hypersonic missiles and aircraft carriers, as denying this smacks of a fairy tale told to children.

- China has been increasingly active in international organizations such as the United Nations, and has been working to establish new institutions such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. What is China’s broader strategic vision for its role on the global stage, and how do you see this evolving in the coming years?

On 15 May 1648, the first treaty of the Peace of Westphalia was signed in Osnabrück by the Protestant princes, marking the end of the conflict between Sweden and the Habsburg Empire. Later, on 24 October 1648, the Catholic princes signed two additional treaties in Münster.

Westphalia – and, to an even greater extent, the Congress of Vienna (1 November 1814 – 9 June 1815) that replaced it – was also based on three pillars, namely multipolarism, a balance of powers and a concert of powers, which mainly meant the importance of the great powers: Austria, Prussia, Russia and the United Kingdom. In many respects, the same principles were characteristic of the Yalta-Potsdam system, which determined relations between the two superpowers during the Cold War. The rules of international law were respected mainly because there was a force behind them that could not be ignored. This is the reason why peace reigned on the European continent, and the interests of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and the United States of America clashed mainly in the countries on the periphery – i.e. by shifting the Second Thirty Years’ War (1914-1945) to the countries of the Third World and the Balkans, so that the war industries in the West and in the East would anyway have their theatres and market outlets. Little could the People’s Republic of China do by calling the former social-imperialists and the latter imperialists tout court, and branding them both as hegemonists.

As stated by Henry Kissinger, when in the early 1970s the People’s Republic of China embarked on its re-entry into the international diplomatic system at Zhou Enlai’s initiative and, at the end of that decade, on its full entry into the international scene thanks to Deng Xiaoping, its human and economic potential was vast, but its technology and actual power were relatively limited.

China’s growing economic and strategic capabilities have meanwhile forced the United States to measure up – for the first time in its history – to a geopolitical competitor whose resources are potentially comparable to its own.

Each side sees itself as an unicum, but in a different way. The United States acts on the assumption that its values are universally applicable and will eventually be adopted everywhere. China, on the other hand, expects that the uniqueness of its ultra-millennial civilisation and impressive economic leap forward will inspire other countries to emulate it so as to break free from imperialist domination and show respect for Chinese priorities.

Both the US missionary impulse based on a sort of “manifest destiny” and the Chinese sense of grandeur and cultural eminence – of China as such, including Taiwan – imply a kind of subordination-fear of each other. Due to the nature of their economies and high technology, each country is affecting what the other has hitherto considered its core interests.

In the 21st century China seems to have embarked on playing an international role to which it considers itself entitled by its achievements over the millennia. The United States, on the other hand, is acting to project power, purpose, and diplomacy around the world to maintain a global balance established in its post-war experience, responding to tangible and imaginary challenges to this world order.

For both sides’ leaders, these security requirements seem evident, and are supported by their respective publics. Yet security is only part of the grand discourse. The key issue for the planet’s existence is whether the two giants can learn to combine the inevitable strategic rivalry with a concept and practice of coexistence. It is for this reason that China is increasingly active within international organisations to stabilise its role on the evolving global scene.

- What is your perspective on the potential military applications of China’s space program, such as anti-satellite weapons or space-based surveillance systems?

Let us start by saying that the successes of the advanced Soviet missile war industry of the 1950s-1960s and the refined and extremely rich US military technology of the 1960s-1970s were certainly not due to moral missions in favour of knowledge and mankind or anything else, but were an extreme arms race. Denying this is tantamount to telling jokes in a bar. The same holds true for President Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative in the 1980s. President Reagan at least had the good taste not to describe it with do-gooding rhetoric in favour of science and the welfare of peoples on Earth. Moreover, anti-satellite weapons and space intelligence systems or space-based surveillance, as you call it, have existed for decades.

Today the People’s Republic of China is also capable of navigating in space. One thing must be said: the competition is based not on the hope of reaching Mare Tranquillitatis (the Sea of Tranquillity) on the Moon or Utopia Planitia (the Nowhere Land Plain) on Mars, and from there bombing the District of Columbia.

Let us go back in time. Faced with the US and Soviet successes in the space field, Mao Zedong in the 1960s was shocked and asked: “How can we be considered a powerful country? We cannot even shoot a potato into space!!!”

Years later, in the late 1970s, Deng Xiaoping replied to him: “If China had not a nuclear or a hydrogen bomb or had not launched satellites since the 1960s, it would not be called an important and greatly influential country and would not have its current international status”. Therefore, in the 21st century, manned space flight represents all of this.

On 25 December 2021, NASA launched the James Webb space telescope for infrared astronomy, capable of analyses considered impossible until a few years ago, i.e. taking detailed, full-colour pictures of an exoplanet. The James Webb telescope is completely different from those in space. It gives the possibility to observe the reflected light of exoplanets and the electromagnetic spectrum in order to detect potential biological or mineral traces. The future lies in space research, not in Star Wars, as well as in reaching the nearest asteroids and meteorites, and looking for habitable exoplanets in the distant but not remote future. On our Earth, mineral raw materials are running out. The same holds true for water, and therefore space exploration today is not aimed to wipe the opponent off the face of the earth, but to collaborate between superpowers to seek alternatives to the depletion of land and even water resources that currently – and we do not know yet for how long – permit these high levels of technology. The Chinese space programme aims primarily at this and not at destroying potential opponents, without whom the real conquest of space would not be possible.

- How do you see China and Russia collaborating or competing in areas such as energy, technology, and military affairs?

From the tsarist expansion to the subsequent unequal treaties, until the crisis in the 1960s with the Soviet Union – as the latter had excluded it from the possibility of having the nuclear weapon, fearing the populous and enthusiastic heavy-handed neighbour that later brilliantly shifted the issue to the ideological side, thus eroding Soviet power over many of the world’s ruling and non-ruling Communist parties – China, per se – and I am not just referring to the People’s Republic of China (1949-2023) – had always held off first St Petersburg and then the Kremlin. For China – indeed for the Middle Empire – a strong Russia on the border is a disadvantage, but a weak neighbour which, in turn, can be other-directed by third parties – as happened in the 1990s – is also dangerous. The traditional solution of China’s two-thousand-year-old diplomacy is to seek a balance that does not create crises in Eurasia which, as is well known, is the last resource reservoir on planet Earth. In 2021, on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the establishment of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation and the signing of the Sino-Russian Treaty of Good Neighbourliness, Friendship and Cooperation, relations between the two countries entered their third decade of stability without any form of military alliance, or even Chinese support for the invasion of Ukraine. It should also be said that arms sales to one side are counterbalanced by the other side’s same action.

- The United States has accused China of being a major threat to its cybersecurity, with allegations of state-sponsored hacking and cyber espionage. What is your perspective on this accusation, and how do you see the cybersecurity relationship between the US and China evolving in the future?

From time immemorial, intelligence or espionage, or whatever you call it, has always been adopted simultaneously by the parties involved, with the most efficient means of the time, ranging from smoke signals to sympathetic ink, from cartographic cryptography to Enigma, from spy planes to the famous James Bond-style mini cameras. Today it is the same: the fear of espionage – be it cyber, cybernetic or satellite espionage – is two-faced, and the accusations of one side to the other are mirrored by those of the other to the one side. They therefore cancel each other with the result that whoever is better equipped knows more than the one who is less prepared. There are no victims and oppressors, there are no good guys and bad guys. There is only the reason of State, as Machiavelli teaches us.

- Russia has been accused of meddling in the 2016 US Presidential election through hacking and cyber espionage. How do you see China’s relationship with Russia in the realm of cybersecurity, and do you think China could be implicated in similar activities?

You know, I am merely a business manager, a geopolitical scholar and a university professor. Part of my answer on China-Russia relations is under point 6. However, in order to fully answer this brilliant but very difficult question of yours, we should address to the highest-ranking and most arcane levels in the USA, Russia and China.

Thank you for the interview.

Giancarlo Elia Valori